The debate about higher value added has been at the centre of economic debates worldwide since the beginning of globalisation.

We have often been critical of the central logic of economic development in Hungary. One key conceptual dichotomy of our analysis has been that Hungary’s growth has has been extensive rather than intensive, meaning that it has relied more on the expansion of employment (in itself a very welcome trend), but at low levels of productivity, and therefore at low wages. There would be a need to switch to an intensive form of development, which would entail raising the value added per person already employed, leading to higher incomes.

The prerequisite for intensive economic growth is a fast increase in human capital, brought about by excellent educational and health systems, the absence of which we have also criticised repeatedly.

❉

Economy minister Márton Nagy has reacted to our criticism. Below is his entire Facebook post:

The main message of his response is that according to him Hungary had already been in an intensive phase of development prior to certain external events, but these caused a temporary stoppage. The external causes he mentions are COVID19, the energy crisis and the Russian invasion of Ukraine (which he calls Russian-Ukranian war).

He attaches a chart, which at first glance seems to back up his argument.

Employment (light blue jagged line, right scale) has increased quite significantly in Hungary, rising from a 57% employment rate in 2010 (the year Fidesz took over) to 75% by 2024. A massive gain in employment, and a very welcome achievement indeed! However, in and of itself this only results in extensive growth.

Therefore Minister Nagy also includes data about the development of productivity. This is indeed a very relevant indicator, as this is how we measure the increase in value added, which would be the sign of intensive development. The minister’s figures indeed reflect growth in value added measured in value added per hour (dark blue continuous line) after 2017, evening out after 2021. The latter would be consistent with the minister’s claim that various external forces have impacted the development of value added, although he does not explain the mechanisms through which this happens. Employment seems to increase in spite of these external effects, why not value added? Through what mechanism exactly does the invasion of Ukraine impact value added per hour in Hungary? It is hard to see how these could possibly be related events.

This, however, is not the main point of our contention.

What we find problematic with the minister’s chart is that it seems to analyse Hungary in a vacuum, without any competitors. However, actual economic development takes place in an international context, where Hungary’s competitors are also developing with time. They also attract and lose jobs, both higher and lower value added.

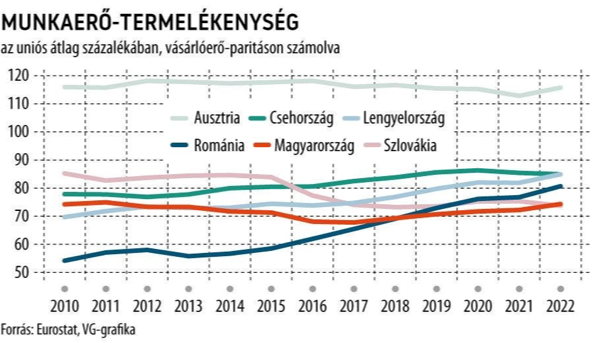

Therefore we need to look at Hungary’s development in an international context. Here is a chart showing productivity in a regional comparison, as a percentage of the EU average, from 2010 to 2022.

Obviously, as productivity across the EU increases as well, the same absolute level of productivity per hour can slide from being high value added to only low value added. One might achieve higher speed initially by riding a horse drawn carriage rather than walking, but if others begin to drive cars, horse drawn carriages suddenly come to be regarded as slow means of transport.

What we see on this second, comparative chart is that even though Hungary’s productivity had indeed begun to grow at an absolute level (as per the minister’s chart) after 2017, in a relative sense this was only enough to keep it at the same level (as per the comparative chart). Hungary’s relative productivity (vis-á-vis the EU average) was 75% back when Fidesz took over in 2010, and it was also 75% as late as 2022. No convergence whatsoever. Running to stand still, like the Red Queen in Alice in Wonderland. Too little absolute productivity gain for intensive economic growth in an international comparison.

The fact that relative convergence would also have been possible in the same time period can be observed by taking a look at the Romanian or the Polish data. Romania (dark blue line) increased from 55% (way below Hungary) to 81% in the same time period, overtaking Hungary in the meantime. Poland (light green line) had also started off below Hungary in 2010, at 70%, then quickly overtook Hungary, kept on converging, and even reached Czech levels at 85% in 2022.

❉

In summary: intensive growth is a relative concept, not simply an absolute one. Hungary’s has not converged, and this is mostly due to its inadequate educational and health systems.

Here you can see our live debate with Minister Nagy:

Book Recommendations